Part 1

Embedded-Archetype Recycling

Introduction

More so than any other medium, the motion picture – also known as film, cinema, and most commonly, movies – has the capacity to convey ideas and themes whilst bypassing the viewer’s awareness of having done so; meaning that even the reception of the content generally remains unperceived, i.e. let alone its affect and techniques thereof. This principle can be observed by the substratum of archetypal themes from which movie* narratives are constructed upon; by the industrial recycling of these archetypes, evident in movies that are differentiated by time and genre; and by the common obliviousness to embedded elements and the pervasiveness of this practice.

*Although most of this article concerns movies, the discussion generally applies to television fiction too, particularly since it has become more cinematic in recent years. Movie narratives, however, are the primary form of embedded-archetype recycling.

I have termed the principle behind this practice ‘embedded-archetype recycling’, where “archetype” refers to a type of character or theme that is ancient, or at least pre-modern (hence being adapted into modern form); where “embedded” refers to the concealment of the archetypes within the overt narrative; and where “recycling” refers to the institutional practice of reapplying these archetypes to the narratives of “new” movies (hence, archetypes pervade the medium irrespective of era divergences and genre differences between movies).

The purpose of this article, then, is to highlight the following combination of elements common to the viewing of movies:

- Movies are composed of dual narrative dimensions: an overt narrative and an underlying narrative.

- Underlying narratives are composed of archetypal themes, thus recycling the essences of ancient stories and their elements.

- The technique of embedding harnesses the potency and utilities of archetypal themes by reapplying them through narrative and cinematic techniques.

- The average viewer perceives the latest movies as “new”, in the sense of innovative or unique—oblivious not only to the ancient source of its core elements, but also to the pervasiveness of these elements among the movies he has seen (i.e. he is oblivious to recycling).

More specifically, this article is intended to highlight the formal deceptiveness of the movie medium, whereby populations of educated people habitually watch movies yet without perceiving the institutional recycling of ancient story elements—i.e. elements that underlie the apparent ‘newness’ of successive movies.

This scenario is based upon two principles. Firstly, people generally do not want to view entertainment critically, but rather desire maximum amusement. Secondly, the movie medium itself (and the audio/visual mediums in general) are particularly effective at conveying embedded content, i.e. messages and affectation that bypass the viewer’s awareness—for movies demand a sensual attention, which is thus conducive to distraction from structural aspects and immersion in the display*.

*I found watching the programme “Greatest Ever Movie Blunders” to be good demonstration of this principle, in that it catalogues innumerable instances of “mistakes” in movies – including the most popular and acclaimed movies – most of which are clearly visible—and yet most of which I had not noticed before.

The remainder of Part 1 comprises examples of archetypal embedding that have been most salient to my mind, classified by The Epic, The Biblical, and The Hero’s Journey; and which represent the accrual of casual observations during years of enjoying movies—or more specifically, during the years of watching movies consciously.

The discussions that follow are not made as analysis, although they do contain analysis; and indeed, I have deliberately not studied or researched* any of the movies discussed, as film analysis is not my motive here. Rather, the entirety of this article represents a synthesis of thematically-accrued observations, including descriptions of the original causations and reflections of those observations, which are offered as a source of insight into the experience of conscious movie-watching. Finally, Part 2: BONUS FEATURES is an addendum of related discussions, all of which are referenced in Part 1.

*During the writing process, I did however refresh my memory by re-watching a few of these movies, as well as consulting the plot descriptions and scripts when needed.

Varieties of Embedded Archetypes

The Epic

The Gilgameshness of L.A. Confidental

When L.A. Confidential (1997) was released in the late nineties, it was a high-profile movie that my friends and I (then moviegoing eighteen-year-olds) went eagerly to see, expectations well raised by the promotional media. At that age, my enjoyment of movies was still on a purely entertainment basis, meaning a simple one; hence I viewed the film* with what could be called a ‘one-dimensional level of perception’ and was happily entertained in that respect.

*I find it useful to distinguish the nuance between a “movie” and a “film”, in that I perceive the latter to be more mature in composition (with regards to intellect and sophistication, rather than explicit content). L.A. Confidential felt more in between the two, although it leaned enough to the mature side to affect a film-like experience.

Twenty years later (four years prior to this article), my enjoyment of movies had gradually moved towards the critical dimension, in that I had become conscious of and more attentive to perceiving the underlying themes of movies, as well as the affective techniques of movies and the social significance thereof. As I had not watched L.A. Confidential since its cinematic release and having noticed its status as a classic (being widely considered as one of the best nineties movies), I looked forward to re-watching it, particularly since I could not recall much of the film and was curious as to how I would perceive it now.

My reception of it the second time around was that the film is undoubtedly an excellent one, although not quite a great one, as it lacks that indefinable quality of ‘magic’ often attributed to those movies of genuine greatness. Of more interest here, however, is that when the credits began to roll, I turned my attention to the thought “What is this film about?” As I casually recounted the main elements and developments of the story in my mind, a minute or so of this triggered a reminiscence of another story: The Epic of Gilgamesh.

With a sense of curiosity, I consulted my Dictionary of Mythology to read the synopsis of the Babylonian epic story (circa 2100-1200 BC). And sure enough, the core plot elements and developments I had recounted from L.A. Confidential – those very elements that had triggered this reminiscence – were key aspects of the The Epic of Gilgamesh. The L.A. Confidential rendition of these core elements is as follows:

- The flawed hero protagonist (Ed Exley, played by Guy Pearce), clashes with…

- A newly encountered barbaric rival (Bud White, played by Russell Crowe), over…

- A seductive harlot (Lynn Bracken, played by Kim Basinger); whose affections aid the respective development of each character, such that…

- The opposing characters become friends and collaborate to defeat the common enemy (Capt. Dudley Smith, played by James Cromwell), resulting in…

- The saddening death* of Bud.

*To be elaborated shortly.

Having read The Epic of Gilgamesh years previously, these elements and their basic thematic construction were thus laying dormant in my mind, in that I had not had any narrative related thoughts about the story—that is, until I re-watched L.A. Confidential. For essentially, the above outline of key plot elements and their thematic relation were already present in The Epic of Gilgamesh, the mythological characters being the protagonist Gilgamesh, the barbarian Enkidu, the harlot Shamhat and the enemy Humbaba.

I did, however, immediately notice an exception to this core structure that is also an interesting one: Whereas Enkidu dies, his corresponding character Bud does not die actually but dies symbolically, in what I call the technique of cinematic apophasis*. By this term I mean that the scene leads the viewer to believe that Bud is dead, such that one is affected as if it had happened. In other words, the conceit is done quite thoroughly, which is not usually the case with this device; hence by the time Bud’s survival is revealed (which felt like a good five minutes later), the viewer has already (dis)regarded the character as dead.

*I use the term “apophasis” to mean a rhetorical device in which the speaker promotes a notion under the guise of denying it. Hence, I use “cinematic apophasis” to refer to what appears to me as the filmic equivalent of the rhetorical device—specifically, in its analogous intent, ruse, and affect.

What makes this manner of resolution interesting is that it neatly demonstrates (with regards to the recycling of embedded archetypes) the tailoring of ancient core elements to fit the modern form whilst yet retaining their essence. In this case, the apophatic technique is employed to satisfy the almost inviolable Hollywood convention of the “happy ending”.

In addition to the above, reading the synopsis of The Epic of Gilgamesh actually triggered a reminiscence of the story of L.A. Confidential; namely, that Enkidu enters the underworld to retrieve some objects: For in L.A. Confidential, Bud enters the crawl space beneath a house where he finds a dead body, and which serves as evidence towards solving the case together with Ed. Thus, in the context of the other correspondences, this character having this experience is clearly another aspect of the Gilgamesh story appropriated by L.A. Confidential.

After having confirmed this case of an embedded archetypal theme (i.e. a few years ago as of writing) I then sought an analysis of L.A. Confidential in this context, expecting that a film analyst (or at least an analytical movie buff) would have made this connection, hopefully with some insightful commentary. Surprisingly, given the movie’s high status, I found no such analysis or even reference to this connection; and having made another search as I write this article, I still find no mention of this connection.

Regardless of this lack of acknowledgement, the abundance of academic film analysis that reveals embedded archetypes is clearly indicative of an institutional practice within the movie industry (although film analysts do not admit this, conventionally – that is, tactfully – evading the overarching correspondences between their observations). For if one seeks substantial analyses of movies on a regular basis, the practice I refer to here as “embedding” will be encountered with such regularity that its institutionality is implied by it.

Typically, analysts and artists (i.e. writers/directors) contextualize acknowledgements of embedding within a frame of particularization, meaning that instances of the embedding are revealed in isolation; and phenomenalization, meaning that the effect is spoken of not as an intentional technique, but as if it is an epiphenomena of the artistic process—which often, is deemed as the unintended influence of the artist’s “unconscious”.

Furthermore, the explicit admissions (i.e. by the artistic creators) of embedding are themselves frequent enough to indicate that the technique is an institutional practice of the movie industry. An illustrative example is the case of the television series The Wire (2002-2008), which was widely hailed as one of the best TV dramas of all time. Prior to having watched any of the show, I had heard a news story based on the comments of it creator David Simon, who openly admitted to having “ripped off the Greeks”, i.e. in revealing that the plots of The Wire were derived from the plays of ancient Greek tragedy. Thus officially, one of the “greatest TV shows of all time” is basically a postmodernization of ancient stories, hence making it exemplary here on two counts: of Hollywood* recycling archetypal themes; and of viewers’ perception of the product as “new”.

*I am using the word “Hollywood” in this article to refer to the industry of movie and televised fiction series production in a general and collective sense, i.e. incorporating all of their media forms (terrestrial, satellite, streaming, etc).

The Biblical

The “Something” About Mary

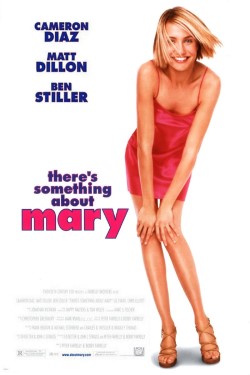

Not during its cinematic release nor my subsequent re-viewing of There’s Something About Mary (1998) did I give any thought to the themes that underlie this screwball comedy. However, during my last viewing a few years ago, a single word in this movie prompted my attention: Magda.

For in There’s Something About Mary, the neighbour and friend of Mary is called “Magda”—a name which seemed odd to me upon hearing it, hence prompting me to wonder why the writers came up with this name. In briefly contemplating what this name could mean, the concurrence of the names “Mary” and “Magda” triggered an association: Mary Magdalene*—from which another association immediately came to mind: The Virgin Mary. I now began to consider the titular Mary with these elements in mind; and in so doing, a prominent theme of the story and a noticeable characteristic of Mary resonated with one of these elements: the virginity of the biblical Mary and the implicit chastity of the movie Mary.

*I would later learn that “Magda” is indeed the shortened name for “Magdalene”.

Being categorized as a “sex comedy”, the plot of There’s Something About Mary is a slew of different men competing for the love of Mary who – being played by Cameron Diaz – is undoubtedly “a fox”, as the infatuated (pur)suitors mention repeatedly. However, something (read: “Something”) which I had not consciously noticed, but must have subconsciously perceived, was that Mary is never seen to be sexual with any of them, nor is there ever an indication that sexual activity has taken place—which is very odd for a 15-Rated “sex comedy”. There are four scenes featuring moderate kissing, one of which emphasizes Mary’s repulsion in response to the guy’s sexual style of kissing, from which she pulls away and says “Whoa, whoa, how’s my stomach taste?”

Another point of interest is that the protagonist Ted – the true good guy who, of course, ends up with Mary at the finale – experiences a series of horrible ‘accidents’ during his pursuit of her—most of which are sexual related:

- The pre-prom date visit at Mary’s house during which, whilst taking a leak, Ted inadvertently gives the impression of masturbating whilst watching Mary through her window as she dresses—the ensuing reaction causing him to get his genitals caught in his zipper.

- The night drive to reunite with his high school love, during which Ted inadvertently falls into a homosexual fest at a rest stop—and as a result, is imprisoned to find himself in another homosexual position, i.e. sleeping with an imposingly large man cuddling him.

- The date with Mary, during which Magda’s doped-up dog bites onto Ted’s genitals.

- A following date in which Ted is about to kiss Mary for the first time… only to have her mentally handicapped brother catch a fishing hook on his mouth, pulling him (painfully) away from her.

Thus, a subtextual (or subsexual) theme of Ted being punished during (read: for) his infatuated pursuit of Mary runs throughout the story—which on a symbolic level, serves to indicate the sacredness of the “Mary” she represents.

On the above basis, I thus consider the “something” about Mary as an allusion to the embedded archetype of The Virgin Mary. While I didn’t notice anything else within the movie that relates to this biblical context, I did now notice an aspect of the iconic movie poster as being related: the unnatural pose of Mary, pushing her knees together, bending to place her hands over them in doing so. Indeed, on reflection, this aspect is precisely what makes that image iconic.

In harmony with the aforementioned allusions, then, the poster image pose symbolically alludes to Mary’s chastity—in a secular postmodern sense of “chastity”, of course. And thus, There’s Something About Mary presents another example of Hollywood’s institutional recycling of ancient and traditional archetypes into modern secular form.

As with the Gilgameshness of L.A. Confidential, I was surprised to find no commentary, let alone analysis, on There’s Something About Mary in association with The Virgin Mary. What I did find – and by “find” I mean, what one will be immediately inundated with when attempted to make this search – is variations of the title “There’s Something About […]” concerning either Mary Magdalene and The Virgin Mary, i.e. in no relation to the Cameron Diaz movie. Examples include the Something About Mary Magdalene (2007) documentary; There’s Something About the Virgin Mary (2017) documentary; a movie within The Simpsons entitled There’s Something About Mary Magdalene; and more generally, a variety of journalists’ title references to the “something”ness about either of these biblical women. Thus, it seems that the movie’s allusion to the biblical Mary is not acknowledged but rather is itself alluded to, in a kind of reciprocal allusiveness between artists and mediators.

These interrelated practices of both art and media serve to facilitate the industrial recycling of archetypes that is characteristic of the modern age, i.e. the subliminal reapplication of archetypal themes towards the progressive agenda of secular ideology. As the above example illustrates, such embedding is unilaterally ignored by movie commentators, being those who profess to interpret art and media for the lay populace*; and concomitantly, via seemingly unrelated media, the embedding technique is obfuscated whilst its embedded content is reinforced.—Thus is how the “something” about Movies is continuously effectual.

*To be clear, movie review journalists and academic analysts are generally very good at their work, which I enjoy consulting often. However, the point here – also being a fundamental theme of this article – is that the contextual dimension of the embedded narrative is unilaterally obscured, due to its discommoding implications.

The Platoon, Temptation, and Passion of Christ (in that order)

Jesus Christ! Just how many movies are embedded with Christ symbolism!?—A lot of them. Indeed, the sheer frequency of this device is one of the most prominent indications of Hollywood’s archetypal ethos.

Having said this, the regularity of this practice became apparent to me due not to direct recognition, but by occasionally reading film analyses; for in so doing, revealed Christ symbolism became a recurring theme, despite that the analyses ranged all types of movies.

A most obvious symbolic element in this regard is the crucifixion pose, which is usually applied to symbolise the death of the hero/protagonist, whose post-“death” life thus symbolises his “resurrection”. Or, perhaps less frequently, the crucifixion pose alludes to the “sacrificial” significance (in a Christ sense) of a heroic character’s actual death.

A most memorable example of the latter case is the film Platoon (1986), the iconic poster of which I presume is familiar even to those who haven’t seen the film. The image is of Sgt. Elias, played by Willem Dafoe, on his knees with his hands raised aloft, as if suspended in crucifixion. To this day I can still recall the childhood experience of first seeing a large billboard of this film, which affected a distinct sense of dread-yet-intrigue (which I now perceive as being engendered by the visual connotation of horror-yet-profundity).

Re-watching this film a few years ago, the symbolic Christ role of the character Elias (within the context of the platoon and its story) became apparent to me, though not due my conscious attention to such themes or symbolism. My viewing frame of mind related to the social commentary of the film (such as its anti-war sentiment), as well as the techniques by which it was conveyed (the score being a prominent aspect in this regard). However, in a manner similar to the “Magda” signification in There’s Something About Mary, I was alerted to the possible presence of a Christ archetype by one line – an even more suggestive one in this case – spoken in reference to Elias: “[The] guy’s in here three years, he thinks he’s Jesus f***ing Christ […]”*

*As I will address shortly, this association immediately triggered an interrelated association—which triggered a parallel association(!)

The underlying theme of the film is not about the Vietnam war, or even war in general, but the conflict between Evil and Good, as personified respectively by the characters of Platoon Sergeant Barnes (Tom Berenger) and Sgt. Elias—the latter being the Squad Leader of the newly-arrived rookie soldier Chris Taylor (Charlie Sheen), who plays the protagonist torn between the opposing ethics of these two conflicting leaders.

Throughout the story, Dafoe’s character risks his reputation and ultimately his safety within the platoon to do what is right, above all the occasions in which he actively opposes acts of wrongdoing by other soldiers, most crucially Barnes. The culmination of this conflict between Elias and Barnes is engineered by the latter in sabotaging the former (without the knowledge of the platoon), resulting in the iconic scene of Elias being gunned-down as he tries to escape the swarm of enemy soldiers, his body forming a crucifixion pose before it collapses. Thus, Dafoe’s Elias plays the sacrificial Christ role to the satanically cynical Barnes’ in dying for the sins of all men, represented here by the widespread inhumanity of war.

This embedded Satan vs. Christ theme is highlighted by Barnes’ polemic to Elias’ squad, as they were heatedly discussing whether or not they should – or could – kill Barnes to avenge their leader’s death:

Barnes: Are you smoking this shit so’s to escape from reality? Me, I don’t need this shit. I am reality. There’s the way it ought to be, and there’s the way it is. Elias was full of shit. Elias was a crusader. Now, I got no fight… with any man who does what he’s told. But when he don’t, the machine breaks down. And when the machine breaks down, we break down. And I ain’t gonna allow that… in any of you. Not one.

Taylor eventually does kill Barnes, less to avenge Elias than to eradicate this diabolical source of cruelty and injustice. After he does so, the film ends with his voiceover narration that again highlights the theme:

Taylor: I think now, looking back, we did not fight the enemy, we fought ourselves. The enemy was in us. The war is over for me now, but it will always be there, the rest of my days. As I’m sure Elias will be, fighting with Barnes for what Rhah called “possession of my soul.” There are times since, I’ve felt like a child, born of those two fathers. […]

Given the multiple signifiers of Dafoe’s Christ role in Platoon (to which can be added the Christian cross Elias wears around his neck) it is not surprising to find that this connection seems to be well represented by film analysts, at least as indicated by the immediate search results. Rather than film analysis, however, of more interest here is a particular technique by which embedded themes are subtly reinforced, as indicated by the “alerting” instance previously described. This technique I term the oblique reference.

If one pays attention, it will be observed that movies embedded with Christian themes often employ the calculated scripting of the words “Jesus”, “Christ”, “God”, and combinations thereof – typically in the form of the colloquial expressions composed by those words – so as to subliminally associate those elements within the viewer’s mind. Although not all analysts point this device out, a few good illustrations are sufficient to make one aware of the technique which, henceforth, will be more readily recognized when encountered in movies*†. And although this subliminal technique is not exclusive to Christian themes, this particular usage seems to predominate in movie design, or is at least the most noticeable.

*Indeed, I only became aware of this technique by the observation of a film analyst, although I don’t recall the author or movie concerned—which is the point: for once a technique has been revealed, the principle – if indeed it is a principle – will be perceived by subsequent instances of recognition.

†Case in point: the bathroom scene in There’s Something About Mary, during which characters’ reactions to Ted’s zipped-up genitals include a “Jesus!” and an “oh God!”, as well as one “how in heaven…!” and two instances of “how in the hell…!”

To return to the oblique reference in Platoon, the immediate association it triggered in my mind was not actually concerning Elias but concerning Willem Dafoe; for in recent years, I had become aware of his starring role in The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), a religious drama directed by Martin Scorsese*. Thus, I realized, it can be said that soon after his character was accused of ‘acting like Christ’, followed by his symbolic crucifixion of Christ—Dafoe then became Christ.

*Scorsese’s career work strangely combines a fixation on the themes of faith, guilt, and redemption, specifically in the Catholic sense; with those of machismo, nihilism, and crime, primarily in the gangster sense (and especially in the f***ing profanity sense!)

Incidentally, the recognition of Dafoe’s Christ-role in Platoon made me intrigued to see his actual portrayal of Christ in the film The Last Temptation of Christ—a thought which triggered a parallel association: for a symbolized Christ in a war film, followed by a portrayed Christ in a religious drama, evoked a reminiscence of the actor Jim Caviezel in his roles as a platoon soldier in The Thin Red Line (1998), which I had seen; and his portrayal of Christ in The Passion of the Christ (2004), which I had not*.

*As with The Last Temptation of Christ, I was now intrigued to watch The Passion of the Christ. After having done so, “The Passion” must be described as a film-length torture-session of torturous detail—the result of which (aside from a slew of controversies) is Academy Award nominations for Best Makeup and Best Cinematography!

In the The Thin Red Line, Caviezel – like Dafoe – plays a soldier whose sense of rightness and integrity, backed by compassionate leadership qualities, makes him stand out from all the other characters. But more than this, Caviezel’s character – again like Dafoe’s – meets his death in the very particular manner of being engulfed by the enemy on his own, such that his death is not instant but is harrowingly imminent. And in both cases, but in different ways, their deaths symbolically represent a Chris-like sacrifice.

Jim Caviezel (‘J.C.’—just coincidentally) embodies ‘Christness’ in this film; or, more accurately, a proto-Christ character. Primarily, this character (named Pvt. Robert E. Lee Witt) is formed by the distinguishing qualities he displays throughout: those of innocence, joy, spirituality, responsibility (determined by conscience as opposed to authority), kindness, compassion, courage (including the proclivity to confront profound doubts), and an intuited faith in goodness over evil.

In fact, Caviezel is more Christ-like in The Thin Red Line than Dafoe is in The Last Temptation of Christ (and I’m talking no contest!*)—he exudes Christness to such an extent that it may even be possible to illustrate it by a sequence of still shots from the film†. For even from the very beginning of the film, the first character shown is Witt joyfully rowing a boat towards the shore, smiling as he watches the (off screen) native Melanesians go about their lives on land, in a shot soundtracked by choral music‡.

*Admittedly, Scorsese’s depiction could be called ‘Jesus Christ – The Schizophrenic Version’; therefore, it seems to not be saying much that Caviezel’s character in The Thin Red Line out-Christs Dafoe’s in The Last Temptation of Christ. Hence, I will stress that Caviezel’s character in that film is distinguishingly proto-Christ-like with respect to benevolent movie characters in general.

†Seeing as Google Images returned plenty of good screen shots, I made a fairly quick attempt at this illustration which I have addended to the article (see Part 2, “The Christness of Jim Caviezel in The Thin Red Line”).

‡Choral music is conventionally used in movies to affect the (viewer’s) experience of a scene with a spiritual tone; as well as to connote Christian themes, which of course choral music as a form is historically (i.e. originally) associated with. Thus, this artistic practice can be considered as an aural form of embedded-archetype recycling, as it can be clearly observed that the technique is institutional in movie production.

After Witt is shown enjoying his interactions with the natives – his innocence akin to a child-like purity of fascination – the next scene reveals that he had gone AWOL to do so. Back on the troopship, Witt is reprimanded by his Sergeant Edward Welsh (Sean Penn), who expresses his tiresomeness of Witt’s characteristic disobedience—this being the first of several dialogues between the two men over the course of the film. Towards the end of the scene occurs an exchange that sets in motion an underlying theme, not only between the two characters but in Witt’s character arc, which also forms the philosophical locus of the film:

Welsh: In this world… a man himself is nothing. And there ain’t no world but this one.

Witt: You’re wrong there, Top. I seen another world. Sometimes I think it was just… my imagination.

Welsh: Well, then you’ve seen things I never will.

Late in the film, after at least one more key dialogue between the two, another exchange indicates that Witt’s spirit has somewhat affected Welsh’s:

Welsh: Hey, Witt. Who you making trouble for today?

Witt: What d’you mean?

Welsh: Well, isn’t that what you like to do? Turn left when they say go right? Why are you such a troublemaker, Witt?

Witt: You care about me, don’t you, sarge, I always felt like you did. Why do you always make yourself out like a rock? One day I can come up and talk to you and the next day it’s like we never even met. (pause) Lonely house now. You ever get lonely?

Welsh: Only around people.

Witt: (softer) Only around people.

Welsh: You still believing in the beautiful light, are you? How do you do that? You’re a magician to me.

Witt: I still see a spark in you.

Witt: (voice over) One man looks at a dying bird and thinks there’s nothing but unanswered pain. That death’s got the final word, it’s laughing at him. Another man sees that same bird, feels the glory, feels something smiling through it.*

*A line which is reminiscent of Dafoe’s in The Last Temptation of Christ:

Jesus: Everything’s a part of God. When I see an ant, when I look at his shiny black eye… you know what I see? I see the face of God.

Judas: You’re not afraid of dying?

Jesus: Why should I be? Death isn’t a door that closes, it opens. It opens and you go through it.

The essence of Caviezel’s proto-Christ character in The Thin Red Line runs throughout the film, conveyed by a combination of performance, dialogue, story, cinematography, score, and editing (particularly voiceover narration). Rather than attempt to vividly describe or illustrate it I have merely tried to indicate it, which is sufficient for the purposes of this article and to which I add the following observations.

In Platoon, the death of Dafoe’s Elias represents a symbolic sacrifice for the sins of humanity (i.e. as that of Christ’s), which the film represents by its focus on the inhumanity of war. In The Thin Red Line, the death of Caviezel’s Witt near the end also represents this symbolic sacrifice, only in a different manner that is in harmony with this particular war film, being of a distinctly different type and style than Platoon (and indeed war films in general).

The sacrifice begins by Witt’s volunteering – visibly out of sheer concern – to accompany two weaker soldiers who have just been given orders to carry out a reconnaissance mission likely to result in their deaths. During the mission, one of them dies and Witt saves the other—by sending him to report back while Witt holds-off the advancing enemy platoon. As he does this, Witt finds himself literally surrounded by enemy soldiers—his response to which produces a mesmerizing scene for the audience: Witt stands still, gun lowered, intensely observing the experience as if to confront its implications spiritually—which is to say, the spiritual implications of death and the manner in which one confronts it. It is apparent, however, that enemy do not intend to kill him, but rather are imploring him to surrender for he has not dropped his gun (as indicated by their barked foreign words towards him). Thus, in suddenly raising his gun, Witt forces them to kill him—an action which, in the context of his character arc and his demeanour in this scene, makes more sense as a Christo-symbolic sacrifice on a narrative level, than any motivational one on a character level.

The Thin Red Line is certainly not the average war film, for the violence and horror is measured to serve as the background for the philosophical motive of the work, which is palpably existentialist*. This motive is enhanced by an ensemble cast with a narration style of multiple voiceovers, whereby the personal thoughts of several different soldiers are periodically revealed, all of which are existentially philosophical and deeply meaningful. Within this ensemble, however, it is quite clear that Caviezel’s character is cut as the quasi-protagonist of the underlying narrative, in that Witt’s personal arc serves as the philosophical (and spiritual) polestar of the film’s existential message. Thus, Caviezel’s role serves a Christ-esque function analogous to, yet inherently distinct from, that of Dafoe’s in Platoon.

*It is, however, not as straightforward as that; for Witt’s character arc represents a secularization of Christian spirituality—particularly, by the manner in which the character’s dialogue and narration are strictly allusive of belief in an afterlife. With that said, ‘Existential Now’ comes to mind as a fitting satirical title for the film.

To return to the two portrayals of Christ (Dafoe in Temptation and Caviezel in Passion), these of course are not instances of archetypal embedding, for the archetypes are explicit. However, that the actors’ roles of an embedded Christ prefigured* their roles of a portrayed Christ serves to highlight a corollary institutional practice in the movie industry, which I will term the planted archetype. By this term is meant that – within the discreet conventions of movie production that serve to form a Hollywood “shared universe”† – the archetypal roles of major movies are embedded in the preceding movie(s) of that actor. Hence, on a subliminal level, the performance of that archetype is felt to be an outgrowth (i.e. a natural development) of the actor’s aggregated filmic persona—thereby enhancing the affectivity of the role and, more broadly, reinforcing the receptiveness to subliminal affectation.

*Interestingly, Willem Dafoe plays the unnamed lead role in the film Antichrist (2009). Thus, Dafoe’s movie career contains a Christ-arc, beginning with a symbolic Christ (Platoon); to a portrayed Christ (The Last Temptation of Christ); to an allusive inversion of Christ (Antichrist). Decidedly, I have not seen Antichrist, for it has the unpleasant distinction of making me wish I could unread its plot description, such is the perverse macabre of that ‘film’. But I mention it to address another variation of the embedded archetype that I term ‘Actor’s role-inversion’, which will be explicated in a dedicated section in Part 2.

†To be addressed in the following subsection.

Thus, the institutionally designed correspondence between actors’ successive movie roles applies the narrative device of “foreshadowing” to the movie medium as a whole, and to an analogous effect. On this point, a brief digression is in order.

The Subliminal Dimension of Artistic Licence

The institutional contrivance of Hollywood to which I refer is a discreet but inferable dimension of the movie industry by which the populace are subtly cued as to the formation of relevant and righteous thoughts, attitudes, and behaviours. To put it simply – and by applying one of Hollywood’s terms to itself – this camouflaged dimension serves to form what I call the ‘Hollywood Reflexive Universe’; and more conveniently, the ‘Hollywoodverse’*.

*The concept of a fictional “shared universe” is explicitly represented by the Marvel Cinematic Universe, whereas it is esoterically represented by the series Black Mirror and the filmography of Quentin Tarantino† (dubbed the “Tarantinoverse”)—thus displaying intra-franchise/artist coordination. The “Hollywoodverse” to which I refer, however, is not esoteric but operational—meaning that coordination is inter-movie/series; that is not intended to be acknowledged (hence it is not); and that the system of coordination is far more elaborate than the ‘miniverses’ within it (e.g. the aforementioned “shared universes”). The structured reflexivity, semiotic devices, and subliminal effects of the Hollywoodverse is a matter beyond the scope of this article, although it will be addressed here to an extent.

†Not to mention Tarantino’s unprecedented and admitted “stealing” (read: recycling) of classic films and genres from all over the place: “I steal from every single movie ever made.”

However, an essential aspect of democratic society is the collective ignorance of this operational dimension of Hollywood’s industry, hence precluding even the recognition of it as potential matter for discussion. Briefly, the reason for this circumstance is that Democracy is based on the pretence of an authentically formed society and culture, which defines and distinguishes itself by opposition to the non-democratic forms of society, i.e. in which a social stratum of leaders dictate the social and cultural criteria. In actuality, however, “democratic” culture is neither dictated per say nor authentically formed, but is discreetly managed and symbolically designed—in other words, as contrived-yet-naturalized as all other societies, including the devout pretence that it is (exceptionally) authentic.

This subject is one that requires a dedicated discussion, especially due to the automaticity with which it is ignored, i.e. in public ‘discourse’; and the extent to which it is misrepresented, i.e. in ‘alternative’ discourse*. Thus, the practice of such influencing techniques is insulated by the institutional pretence of artists, producers, and commentators, who tactfully discuss art production in the distorted context by which its socio-ideological function is obscured; and furthermore, by the “conspiracy theory” media that obfuscates such processes, mainly by cultivating and exclusively citing misrepresentations that serve this false dichotomy. Ultimately, however, it is the reciprocated ignorance of the populace that represents the insulation from awareness of this influence.

*This will be addressed in the section “Paradigms of Movie Interpretation” in Part 2.

Suffice it to say here that the observations made in this article are intended to be usefully insightful and/or illustrative to individuals who are, or desire to be, more critically aware of the movie medium, with respect to its techniques and affects in the context of its social function. Hence, those who are inclined to define such observations of Hollywood praxis in terms of conspiracy – be it in affirmation or refutation of that notion – will presumably misinterpret this article to that end (if indeed they even find reason to read it to the end).

In summary of embedded biblical archetypes, their prevalence in movie narratives (including various forms of audio-visual symbolism) will be observed if one is critically attentive when watching movies; and more so if one supplements this attitude by occasionally reading good analysis. Logically, this pervading presence of biblical themes* and archetypes in mass and even marginal entertainment is at variance with the ostensible ethos and actual customs of secular society, particularly considering its disregard if not disdain for Christianity and the Bible as a source of truth, morals, or inspiration.

*Another prominent biblical theme embedded into the structure of movies is that of Purgatory, which I won’t expand on here. I will however mention two movies of purgatorial sub-narrative that are contrasted in my mind in terms of recognisability: Jacob’s Ladder (1990), a psycho-horror in which the purgatorial theme becomes quite apparent (although remaining symbolic, thus embedded); and Groundhog Day (1993), a comedy-fantasy romance in which I had not recognized the theme until reading a film analyst’s mention of it—after which it became everywhere apparent how integral the purgatory theme is to this movie (which also includes the subtheme of “the seven deadly sins”).

This I suggest is indicative of an eternal principle of Society*: that the art and entertainments of any society primarily serve the psychosocial function of instilling (what I term) The Mythical Paradigm into the collective consciousness, by which the essence and functioning of Society is refracted into a common, mythical conception of it. Thus in other words, fiction reinforces the part-simplified, part-fabricated, essentially illusionary presentation of “The Way the World Works—brought to you by Society™” by which people commonly interpret life and events.

*I have in mind to elaborate on this subject in the future. I have, however, previously touched upon it in my article Fiction: Purpose & Form, based partly on the film Inception (2010)—which (as I explained) is essentially based on the practice of ‘inception’.

The Hero’s Journey

Popularized by Joseph Campbell’s 1949 book The Hero with a Thousand Faces, the “hero’s journey” concept is the perhaps the most representative – or I should say, indicative – of embedded-archetype recycling. The concept is also termed the “monomyth”, which comprises of a 17-stage cycle of mythemes divided into the three acts of Departure, Initiation, and Return. The thesis states that not all renderings of the monomyth apply all of its stages (some stories, for example, focus on only one of the stages), or follow the sequence as outlined; but rather that the schema represents its most complete form.

Having not read the book or researched the subject, I do not know to what Campbell attributed the phenomenon he identified. I expect, however, that his and other proponents of the concept resort to an explanation of the “invisible hand” sort, i.e. so as to account for the seemingly eternal and universal conformity to this formula by all forms of mythical and fictional narrative. If this is the case, the implication concerning fictions writers would be that they “unconsciously” apply the structure or substructures of the monomyth to the formation of their stories, thus creating idiosyncratic iterations of it.

While I personally have no need to verify the monomyth concept, my intuitive perception having encountered it is that the vast majority of mainstream movie narratives are basically modelled on The Hero’s Journey, i.e. to varying degrees. Or, more importantly, the monomyth template is indeed significant with regards to collective and individual psychology as influenced by narrative media. Hence, I expect that most people who are familiar with the monomyth will intuitively sense its aggregational presence among movie narratives in general; and that its application as a template formula in the movie industry would probably be revealed by an extensive analysis (if this has not already been done*).

*The book Myth & the Movies: Discovering the Myth Structure of 50 Unforgettable Films, by Stuart Voytilla, appears to be a substantial study to that end, although I have not read the book.

An example of my intuitive perception in this regard is based on the second stage of the Hero’s Journey: The Refusal of the Call; for this was the aspect of the monomyth that was most resonant with my memories and ongoing perception of movies. This second stage involves the (to be) hero’s refusal to accept The Call to Adventure (the first stage), for a variety of possible ‘reasons’ (i.e. on a character/story level). Below, I discuss the movie scene first evoked in my mind by the “refusal” mytheme.

Rocky: The Hero with a Thousand Sequels

The movie Rocky (1976) is a story based on a journeyman boxer, Rocky Balboa, who is offered the opportunity to fight the heavyweight boxing world champion, Apollo Creed, due to Creed having decided to give a local contender the once-in-a-lifetime chance to fight him. Rocky’s initial response to this incredible opportunity seemed to me, however, incongruent with his character as it had been established thus far in the film—even displeasingly so, due to the depressed manner in which he flatly declines the offer:

Promoter: My proposition’s this. Would you be interested in fighting Apollo Creed for the world heavyweight championship?

Rocky: – No.

In response, the boxing promoter gives a pitch perfect little speech that makes it practically impossible for Rocky to decline, for it emphasizes that America is the “land of opportunity” and that the fight would prove this to the common people—hence also implying that it would be inherently foolish if not cowardly to squander the kind of opportunity most people dream of.*

*See Rocky – The Chance of a Lifetime for the clip of this scene.

Of course, the case of a character who first refuses a challenge and goes on to become the hero can always be ‘explained’ by the writer, particularly in order to account for any apparent incongruity or implausibility with respect to the narrative. But I think this Rocky example is as good as any not so much to validate the monomyth, but to indicate the (tactful) institutional practice of (discreetly) applying a pre-established formula to commercial narrative production—and particularly in consideration of what transpires in the sequel, which I naturally turned my attention to.

Does Rocky II (1979), then, also feature the hero’s “refusal to the call”? Put plainly, an apt title for this sequel would be ‘Rocky II: The Refusal’—for Rocky does not only decline Apollo’s challenge for a rematch but officially retires from boxing. Thence Apollo – being Apollo – is compelled to employ a tactic of publically ridiculing* Rocky back into the ring! Furthermore, Rocky’s “refusal” essentially forms the basis of the plot and constitutes most of the story! Naturally, I then turned my attention to the third Rocky movie.

Apollo Creed vs The Stallion Chicken

The Italian Stallion vs The Chicken

Rocky III (1982) begins in a distinctly differently vein (read: vain) from the previous two: for Rocky is not only the world champion now but he is a world superstar—and the beginning of the movie is clearly designed to establish and emphasise this transformation of the hero. Given this, the “refusal” necessarily takes a different form in this movie in that the superstar champ is not going to refuse any challengers. What thus happens is that Rocky formally accepts the “call” – which arrives in the form of the brutal challenger Clubber Lang – but “refuses” it internally—hence getting defeated in an embarrassingly easy fashion that is not at all representative of his ability or character.

This ‘internal refusal’ even extends to his formal decision to redeem himself via a rematch (in which he is now the challenger), such that it eventually compels his wife (Adrian) to challenge him on this very incongruence, which has become dishearteningly apparent to his whole training team (led by Apollo). During this memorably emotional scene, Adrian challenges Rocky not to accept the “call” but to confront his internal “refusal” and its source—both of which she is determined to draw out of him:

Rocky: Nothing is real if you don’t believe in who you are! I don’t believe in myself no more don’t you understand? When a fighter don’t believe, that’s it! He’s finished, it’s over, that’s it.

Adrian: THAT’S NOT IT!!

Rocky: That is it!

Adrian: Why don’t you tell me the truth?!

Rocky: What are you putting me through, Adrian?! You wanna know the truth? The truth is I don’t want to lose what I’ve got. In the beginning I didn’t care about what happened to me. I’d go in the ring, I’d get busted up, I didn’t care! But now there’s you, there’s the kid. I don’t want to lose what I’ve got!

Adrian: What do we have that can’t be replaced? WHAT?! A house, we’ve got cars, we’ve got MONEY! We got everything but the truth. WHAT’S THE TRUTH, DAMN IT?!

Rocky: I’M AFRAID! ALL RIGHT?! YOU WANT TO HEAR ME SAY IT? You want to break me down? All right, I’m afraid. For the first time in my life, I’m afraid.

Adrian: I’m afraid too. There’s nothing wrong with being afraid […] But it doesn’t matter what I believe because you’re the one that’s got to carry that fear around inside you, afraid that everybody’s going to take things away and afraid that you’re going to be remembered as a coward, that you’re not a man anymore. Well, none of it’s true! But it doesn’t matter if I tell you. It doesn’t matter, because you’re the one that’s gotta settle it. Get rid of it! Because when all the smoke has cleared and everyone’s through chanting your name, it’s just going to be us. And you can’t live like this. We can’t live like this. Cause it’s going to bother you for the rest of your life. Look what it’s doing to you now. Apollo thinks you can do it, so do I. But you gotta want to do it for the right reasons. Not for the guilt over Mickey, not for the people, not for the title, not for money or me, but for you. Just you. Just you alone.

Rocky: And if I lose?

Adrian: Then you lose. But at least you lose with no excuses, no fear. And I know you can live with that.

Rocky: How did you get so tough?

Adrian: I live with a fighter.

Thus is revealed* an indirect form of the Refusal of the Call.

*‘Yo Adrian: you did it!’

In Rocky IV (1985), the refusal is again employed in an indirect form: A newly arrived Soviet boxer Ivan Drago is being touted as the new standard of athleticism*—and Apollo wants to fight him in an exhibition match, out of a sense of patriotic duty and personal challenge. Rocky, however, recognizing the sheer dangerousness of Drago, tries to dissuade Apollo. As they watch a tape of their now classic second fight, Rocky implores Apollo:

*This Cold War-themed movie and its seemingly superhuman villain is reminiscent of Superman IV: The Quest for Peace (1987)—as are (come to think of it) the second and third Rocky and Superman movies with each other. (The section “Paralleled Franchises” in Part 2 features an elaboration on this connection and theme).

Rocky: You don’t want to believe this, but that ain’t us no more. We can’t do that the way we did before. We’re changing. We’re turning into regular people.

Thus is a kind of vicarious refusal. Apollo, of course, swiftly talks Rocky into supporting him (“You’re a great talker, Apollo.”)—and is then swiftly killed in the fight by a ruthless Drago. And, if I remember correctly, the end of Apollo’s funeral* scene cuts straight to the press conference of a very serious Rocky announcing his fight against Drago—thus the hero continues his “journey” (again…)†

*As it will be seen by the time I’ve unravelled this thread, Sly continues to mine narrative out of Apollo long after he killed him off!

†This time with Adrian trying to dissuade him! “It’s suicide. You’ve seen him, you know how strong he is. You CAN’T WIN!”

Since the only thing I remember about Rocky V (1990) is the feeling of never wanting to watch it again (its franchise-tainting reputation being well deserved), I can’t say if Rocky refused the call in this one (although perhaps Stallone should have). Therefore, I will move on to the long-delayed sequel.

Albeit a long sixteen years after Rocky V and at the age of sixty, Stallone made a sixth and “final” Rocky movie, Rocky Balboa (2006), in order to “end” the franchise properly. In this belated sequel, Rocky is now running a small restaurant with his boxing days far behind him; although he is, however, thinking about getting back into the sport. Meanwhile, the undefeated heavyweight champion is in need of a challenge that will gain him popularity. To that end, his promoter visits Rocky to proposition him with a charity exhibition fight in Vegas:

Rocky: I ain’t interested… in getting, like, mangled and embarrassed.

Promoter: No, that’s not gonna happen. Never happen.

Rocky: Truthfully, I was thinking more on a, like… miniscule, small level. You know. Small fights, not big fights. Small fights. Things that… Local. You know what I mean?

Promoter: Not a bad idea. Don’t think of it as big. Think of it like an exhibition. Think of it as a glorified sparring session. Here’s something you’ll like. We’re gonna donate a portion of the gate to charity.

Rocky: That’s always nice.

Promoter: It’s good to give.

Rocky: Yeah. […] I really gotta think about this.

Not a direct “refusal”, but practically as good as one—particularly when considered with the following plot development: a woman named Marie* essentially plays the role that the now deceased Adrian played in Rocky III, i.e. in giving him the push he needed to overcome his doubts and confront the challenge—to accept the “call”.

*In true retro fashion, Marie is the little girl who Rocky walked home in the first movie.

Nine years after the “final” Rocky movie, Stallone – as if drawing on Rocky II – pulls a creative ‘hand-switch’ to continue the franchise with Creed (2015), by way of Apollo’s son Adonis who, predictably, seeks out Rocky to request that he become his trainer. Thus, while Adonis is now the protagonist of the movie, Rocky is still the hero of the saga—i.e. the Rocky saga Stallone has continued via this metafranchise.*

*They don’t call him “Sly” for nothing!

Adonis: I want you to train me.

Rocky: Train ya? I’m no trainer.

Adonis: Be my teacher, then. […] You gotta miss it…

Rocky: Miss it? No. I got it all outta my system, and I don’t look back.

Adonis: Why’d you do it in the first place?

Rocky: I had nothin. Less than nothin.

Adonis: And it gave you something, right? And I’m not talking about the money.

Rocky: Yeah it gave me something. But it made me lose a lot of things too. That’s the thing about boxing, it takes more than it gives, you know?

Adonis: Can say that about life. (beat) Look, it’s something inside of me, telling me I gotta do this. But I’m missing something that can take me to the next level. I think that’s you. You can show me how to do it right.

Rocky: Y’know, Apollo died in my hands. I watched my friend die, knowing I shoulda stopped it. That was what it was; now you’re here. I don’t want it. He wouldn’t either.

Adonis later approaches Rocky again to be his trainer, to which Rocky responds by attempting to dissuade him from being a boxer at all. But later on, of course, Rocky agrees…

In Stallone’s eighth movie of the saga, Creed II (2018), Rocky is still Adonis’ trainer—that is, until Drago junior* shows up looking for a fight, which Adonis is up for but Rocky isn’t:

*The retroism in Creed II is taken to a Stranger Things level, and should more appropriately be titled ‘Rocky IV, II: The Remakesequel’ (see my article Retroverdose—on Strangely Familiar Things for more on this theme).

Rocky: I heard about you and Drago’s kid – That’s not real, right? Somebody’s goofin’.

Adonis: They think it’s real.

Rocky: Is it real for you? You said what? No, right?

Adonis: I didn’t say anything.

Rocky: Ya a real fighter – It’s beneath you.

Adonis: Beneath me? Maybe, but you did it. [meaning that Rocky fought papa Drago].

Rocky: Different – Different reasons – Truth is, there’s pieces I still haven’t found – It’s not worth it. If ya care about what I think, please, move on.

[Later on…]

Adonis: You think I’m going down and not get up? This isn’t yesterday – You don’t have to worry about throwin’ a towel.

Rocky: You should have Lil Duke train you. I think he’ll cover you best an’ ya know him.

Adonis: What about you? What’s the problem?

Rocky: I been through this –

Anthony: He’s afraid.

Rocky: Maybe, wish I was stronger about this, but I’m not.

Adonis: So you’re out?

Rocky: For this. Outside the ring, fight for whatever ya want, but inside, the only thing ya should be fightin’ for is ya life – Good luck.

Needless to say at this point (I hope), Rocky eventually accepts the “call”—and Sly (sigh) has confirmed Creed III (…)

As the above discussion illustrates, the intuitive sense of monomythical presence in movie narratives appears to be accurate on closer inspection, as the Rocky franchise has served to indicate. That this illustration is based upon mere casual observations suggests that research and study would reveal monomythical application in movies to an even far greater degree and scope than indicated here. And indeed, it may even be that the source material (i.e. the scriptures) of the Epic and Christ archetypes discussed here are themselves manifestations of the monomyth (the former more likely so than the latter, I would guess).

In any case, the purpose of this article is to identify and discuss the camouflaged yet evident principles of movie production and perception: that embedded archetypes are continuously recycled—and yet the movies constructed upon them are continuously perceived as “new”.

Part 2

BONUS FEATURES

Part 2 of this article is essentially an addendum of the points raised that I think are relevant enough to elaborate on, and which would have otherwise inflated the main text (i.e. Part 1).

PHOTO GALLERY

The Christness of Jim Caviezel in The Thin Red Line

“[Caviezel] exudes Christness to such an extent that it may even be possible to illustrate it by a sequence of still shots from the film…”

What follows are a selection of still shots of Caviezel’s character Witt from the film The Thin Red Line, selected from those available on Google Images. I have captioned them as best as I can recall the context of the moments; hence there may be one or two inaccuracies in this respect. Nevertheless, I think that these images in concert are sufficiently illustrative of what I have described as the ‘Christness’ of Caviezel’s character in this film, i.e. distinct from his symbolic role, which would only be apparent with a viewing of the film.

Witt: Are you afraid of me?

Native Woman: – Yes.

Witt: – Why?

Native Woman: – Cos you look… You look as an army!

Witt: – I look army?

Native Woman: – Yes.

Witt: Well, that don’t matter.

However, if one watches the scene, it will be seen that the native woman is logically afraid of an ‘army man’ yet intuitively disarmed by the nature of Witt—which, as is the theme here, evinces innocence and goodness.

Note: If I remember correctly, there was another small but indicative moment in which Witt offers a stick of gum to a newly captured prisoner of war; but I could not find a photo of it.

Hopefully this sequence of shots (in chronological order, give or take) with contextualizing captions has been illustrative of the Christness of Jim Caviezel in The Thin Red Line. And, as it happens, more of J.C. in a moment…

CAST BIOS

Actor’s Role-Inversion

“the planted archetype. By this term is meant that – within the discreet conventions of movie production that serve to form a Hollywood “shared universe” – the archetypal roles of major movies are embedded in the preceding movie(s) of that actor. Hence, on a subliminal level, the performance of that archetype is felt to be an outgrowth (i.e. a natural development) of the actor’s aggregated filmic persona—thereby enhancing the affectivity of the role and, more broadly, reinforcing the receptiveness to subliminal affectation.”

“Interestingly, Willem Dafoe plays the unnamed lead role in the film Antichrist (2009). Thus, Dafoe’s movie career contains a Christ-arc, beginning with a symbolic Christ (Platoon); to a portrayed Christ (The Last Temptation of Christ); to an allusive inversion of Christ (Antichrist).”

Briefly mentioned in the article are two principles of the movie industry that I shall now sketch out in more detail.

Firstly, the Hollywood Reflexive Universe, or Hollywoodverse, by which is meant that the undisclosed rules of movie production are systematically coordinated, so as to produce operational yet unperceived trans-narratives that permeate the movie medium; and that this form of concealed organization serves to condition society as to the possible, the ideal, the marginal, and the reprehensible beliefs, attitudes and behaviours that it projects as existent.

Secondly, the device and standard practice of Actor’s role-inversion, as indicated by the incidental mention of Willem Dafoe having portrayed Christ to then star in AntiChrist—and which also serves to illustrate Hollywoodverse technique.

The Dafoe instance is a relatively weak example of Actor’s role-inversion; at least in that having not seen the film, I can’t say that Dafoe’s unnamed character is an embodiment of the antichrist. In any case, I will now share a few of my casual observations that have been most indicative of the Actor’s role-inversion principle.

John Hurt: from Rebel to Dictator

This instance is perhaps the quintessential Actor’s role-inversion, encountered during the first time I watched V for Vendetta (2005). Patently, the movie is a Nineteen Eighty-Four-esque depiction of a dystopian Britain; and hence, I was stunned to see John Hurt portraying the Big Brother-esque authoritarian leader (Adam Sutler), since Hurt is well known for having perfectly portrayed the iconic character of Winston Smith in Nineteen Eighty-Four (1984)—a character that, for generations now, has represented the citizen’s moral and spiritual opposition to totalitarian authority. Thus, Hurt inverts the iconic role in which he personifies resistance to Big Brother—to a role in which he portrays Big Brother by way of blatant allusion.

Patrick McGoohan: from Prisoner to Warden

With respect to the stature of the actor and the familiarity of the roles in question, this instance concerning Patrick McGoohan is not far behind that of John Hurt’s in terms of prominence. Famously, avante-garde television series The Prisoner (1967-1968) was created, written, directed, and starred by McGoohan, who played the titular protagonist of the show. And it is notable here that McGoohan is associated with this iconic role over and above the many other distinguishing roles he has played during his acting career.

The basic plot of The Prisoner is the imprisonment of McGoohan’s character, the unnamed “No. 6”, in a mysterious coastal village—“the Village”; his ongoing resistance to being there; and his battle of wits and fortitude with “No. 2”, who is determined to break his will to escape and (akin to the Big Brother ethos in Nineteen Eighty-Four) to elicit his desire to comply. McGoohan’s portrayal of determination, fortitude, and perhaps above all, wits, is precisely what has made that role an iconic one.

Hence, McGoohan’s role in the classic prison film Escape from Alcatraz (1979) is a prominent instance of Actor’s role-inversion, for he plays the tyrannical prison warden—the unnamed “Warden”; to Clint Eastwood’s Frank Morris, a newly-arrived prisoner whom the warden assures cannot escape Alcatraz. From this plot ensues a battle of wits between them that is reminiscent of that between McGoohan’s No.6 as the determined-to-escape prisoner; and the ‘prison warden’ of the Village, No.2, whose job and desire it is to prevent the prisoner’s escape and indeed, to break his will to do so. Although this contest between a determined warden and an escapist prisoner is more suggested and backgrounded in the film, whereas it was explicit and foregrounded in the series, this aspect of both plots are clearly analogous and thus represents an inversion of roles on McGoohan’s part.

Patrick McGoohan as the prison Warden

Jim Caviezel: from McGoohan to anti-McGoohan

The Prisoner series was remade into a mini-series in 2009, starring Jim Caviezel in the title role, although I have not watched it. I have however seen the movie Escape Plan (2013) in which Caviezel – as did McGoohan – plays the villainous prison warden of a maximum security facility. As in Escape from Alcatraz, a battle of wits develops between the warden and the escape-artist prisoner; although in Escape Plan this aspect is more pronounced—which is not surprising given that the escape planners are Sylvester Stallone and Arnold Schwarzenegger (against a devilish Jim Caviezel*). Thus, Caviezel parallels the role-inversion of McGoohan in a manner that could hardly be any more direct.

*In a bizarre scene during which Schwarzenegger’s character fakes a nervous breakdown – in German – spewing out Bible passages in the process, he actually yells this to Hobbes (Caviezel): “You are the evil one! You are the devil!”

Arnold Schwarzenegger: from Terminator to Impersonator

The most iconic instance of Actor’s role-inversion is undoubtedly Arnold Schwarzenegger in the first two movies of the Terminator franchise; which therefore also carries the distinction of being an intra-franchise inversion*. In The Terminator (1984), Schwarzenegger plays is the Terminator, who has been sent (from the future) to terminate Sara Connor; whilst being opposed by Kyle Reese, who has been sent to protect Sara Connor. In Terminator 2: Judgement Day (1991), however, Schwarzenegger plays the Kyle Reese role in the form of the Terminator; whilst the (original) Terminator role is represented by a newer model of terminator—and whose appearance is entirely unSchwarzeneggerian

*Intra-movie inversion – in relation to Face/Off (1997) – will soon be discussed.

Furthermore, this role-inversion is elaborately concealed – moreover, counter-acted – in the first act of the sequel, wherein the audience’s natural expectations are thoroughly played upon before the iconic inversion is dramatically revealed. This deceit is engineered primarily by the forms, introductions, and initial activities of the Terminator and protector (now a ‘protectonator’) in that they are made to blatantly parallel those of the first movie, i.e. self-reference style. The intended effect is thus to reinforce the audience’s expectation that Schwarzenegger is playing the Terminator ‘respawned’, as it were; whilst the other time-travelled arrival (played by Robert Patrick, who was then unknown) is immediately recognized as representing the new Kyle Reese.

“Get down.”

(…because he’s the Terminator now)

Since these two movies and Schwarzenegger’s Terminator roles in them are so iconic and ingrained into popular culture, the degree to which role changed between them – that is, 180 degrees – can easily be underestimated if not overlooked entirely. But one need only recall his chilling and unsurpassable performance as the cyborg assassin in which he projected a genuine sense of unstoppability. Thus, when Reese explains the Terminator to Sarah

“Listen, and understand! That Terminator is out there! It can’t be bargained with. It can’t be reasoned with. It doesn’t feel pity, or remorse, or fear! And it absolutely will not stop, EVER—until you are dead.”

—Schwarzenegger’s performance has already evinced precisely these qualities for the Terminator, including the sense of being an “it” rather than a “he” – an unstoppable machine – and reinforces it right through to the end, thus instilling the film with a cinematic atmosphere of terror.

Contrast this with the vulnerability of Schwarzenegger’s Terminator character and role in T2; and who admits this vulnerability to his protectee, thus making it clear that the Terminator (now the T-1000) is far superior to him. Thus, Reese’s admitted weakness relative to the Terminator – i.e. Schwarzenegger’s original Terminator – is mimicked by Schwarzenegger’s T2 version of “the Terminator”, i.e. relative to the Terminator of T2, Robert Patrick’s T-1000.

Add to this the plot device of John Connor instructing his guardian cyborg not to terminate anyone, thus literally making him a non-terminating “Terminator”. While the Terminator does, of course, terminate the T-1000 in the end, the point is that Schwarzenegger’s T1 Terminator was a brutal and clinical killer – a true embodiment of the implicit terrors intended to be evoked by that name – whereas his T2 Terminator is more like a robotic bodyguard with humanitarian programming, whose naivety of human and social norms impels his teenage protectee to school him on basic behaviours—not to mention ordering him around like a slave, on occasion.

Another major aspect of this blockbuster inversion is the dimension of self-referencing in T2—its flaunted ‘self-awareness’ of the originator. That Schwarzenegger is cut – in both the costume and cinematographic sense – to resemble a reincarnation of his inimitably terrifying assassinator serves to emphasise the magnitude of this role-inversion—which is then accentuated by Arnie self-parodying and meta-referencing his original Terminator performance.

Finally, the ultimate signifier of this mega-iconic, intra-franchise role-inversion is the inverted recreation of the iconic scene, immortalized by the line: “Come with me if you want to live.”—i.e. whereby Arnie re-enacts Reese saving Sara from Arnie!

Pruitt Taylor Vince: from Diagnosis to Diagnosed

The Actor’s role-inversion is not exclusive to stars or even prominent character actors, but is even applied to journeyman actors, i.e. those actors who one immediately recognizes as having seen in something else, perhaps remembering in which movie or television show it was—yet (generally) without ever having heard of the actor’s name.

Case in point: have you heard of the name Pruitt Taylor Vince? Probably not. But when you see his face, you will probably recognize him, having seen his presence is something or other, perhaps recalling where. Indeed, I had to look up his name for the purpose of this example, which is as follows:

The movie Identity (2003) – described as is “psychological mystery slasher film” – involves an ensemble of characters in an isolated hotel being mysteriously killed off one by one. The plot twist, though, is that these characters do not physically exist but represent the multiple personalities of a schizophrenic murderer, Malcolm Rivers. Upon seeing this character I recognized the actor, yet without being able to recall where I had seen him and being completely unaware of his name—which is Pruitt Taylor Vince. Before I ‘reveal’ his inverted role, the following passage of dialogue – in which the psychiatrist explains the situation to Edward, one of Rivers’ personalities – summarises Vince’s role in Identity:

Dr. Malick: That man, Edward, is Malcolm Rivers. He’s had a very troubled life. He was arrested four years ago… and convicted of the murder of six people in a violent rampage. […] When faced with an intense trauma, a child’s mind may fracture… creating disassociated identities. That’s exactly what happened to Malcolm Rivers. He developed a condition that is commonly known… as Multiple Personality Syndrome.

Edward: Why are you telling me this?

Dr. Malick: Because you, Edward… are one of his personalities.

Not long after seeing Identity I watched The Cell (2000), a sci-fi psycho-horror about scientists who enter the mind of a serial killer to extract the location of his kidnapped victim. Once they capture the killer, they take him to a hospital to have the top forensic M.D. – Dr. Reid – examine his brain via electroencephalogram:

Novak: Make sure he stays cuffed. Two men on him at all times. I don’t want anyone treating him but Reid. Not so much as a thermometer up his ass. Understand?

[…At the hospital]

Reid: Minimal activity in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. And here, the anterior cingulate cortex. (to Novak and Ramsey) It’s what helps distinguish between external and internal stimuli.

Ramsey: What the hell does that mean?

Teddy Lee: (answering for Reid) He’s schizophrenic.

[…]

Reid: In any schizophrenic, these areas would be affected. But in someone with Whalen’s, they’re hit hard and hit fast. […] He has no ties to reality.

And who plays the eminent doctor Reid, diagnosing a serial killer with schizophrenia? Pruitt Taylor Vince, the schizophrenic serial killer in Identity. Vince’s role-inversion is here presented in reverse order, for the reason that this was the order I experienced it (i.e. I happened to watch the older movie after the newer one). Thus, as indicated by the title of this section, this actor’s sequence of inversion is from diagnosing a schizophrenic serial killer to being diagnosed as a schizophrenic serial killer.

“He has no ties to reality.”

He has no ties to reality.

Actor’s Character-Inversion

Actors are also cast to invert the character – in the sense of characteristics – of a role they had previously played. Thus, Sean Penn’s aforementioned character Sergeant Edward Welsh in The Thin Red Line (1998) – the responsible, good-natured, albeit pessimistic sergeant – represents the actor’s character-inversion with respect to his character Sergeant Tony Meserve in Casualties of War (1989)—a character whose imposing wickedness is akin to that of Sergeant Barnes in Platoon (1986).

From Prejudicial Racist to Judical Anti-Racist

A pronounced example of character-inversion is in the movie The Hurricane (1999), in which boxer Rubin ‘Hurricane’ Carter (played by Denzel Washington) is wrongly imprisoned for murder during the 1960’s. Racial prejudice is a central theme of this story, in that Carter’s conviction was engineered from this sentiment; and when the case eventually goes to retrial twenty years later, Carter is again opposed by this concealed racial prejudice.

The retrial, it is made clear, has almost no chance of producing an acquittal. And yet, against all the odds, the judge sees fit to acquit Carter – an admittedly angry black man and brutal fighter who was twice-convicted of the triple-homicide of white men – based on a racially prejudiced conviction—without having seen any substantial evidence to that effect (due to a legitimate stipulation, no new evidence was permitted in the retrial). And who plays the judge that acquits Carter, having somehow discerned that he was convicted based on racial prejudice? None other than Rod Steiger, the actor who won a Best Actor Oscar for his In the Heat of the Night (1967) portrayal of a racist sheriff’s prejudice and contempt for good black cop, played by Sidney Poitier.

In In the Heat of the Night, Steiger’s sheriff Gillespie has authority over Poitier’s inspector Tibbs, thence inhibiting the black man and his work in practice of racial prejudice. This position of authority is also the case in The Hurricane, however the role is different, i.e. that of judge-over-convict rather than sheriff-over-detective; as well as being a small role rather than a starring role. Thus, Steiger’s Oscar-winning role is not inverted; however his character from that role is symbolically inverted—the symbol being the freeing of a black man in response to racial prejudice.*

*Of note with regards to Poitier/Denzel, Best Actor/African Americans: In 2002, Denzel Washington was the second black actor to win an Academy Award for Best Actor, the first being Sidney Poitier in 1964. Denzel began his acceptance speech by a tribute to Poitier, saying “Forty years I’ve been chasing Sidney […] I’ll always be chasing you, Sidney. I’ll always be following in your footsteps. There’s nothing I would rather do, sir.”

From Bastard Guard to Buddy Guard

As if to highlight the character/role-inversion distinction further, The Hurricane also employs a role-inversion of a journeyman actor—but a prominent role-inversion. Observe: Who is the actor Clancy Brown? Most people, I imagine, would not be able to say. But at the same time, most people would immediately recognise his face: for Clancy Brown played the brutal captain of the prison guards in The Shawshank Redemption (1994), Byron Hadley. This character was a ‘bastard’ of the highest order, as well as an integral aspect of the story—and Brown’s portrayal made him (and the film) unforgettable.

Hence, seeing Brown play prison guard Lt. Jimmy Williams in The Hurricane struck me as a ridiculous casting* of this role; for immediately upon the arrival of Ruben Carter – a convicted killer*, no less – Williams treats him with consideration, concern, and even conciliation—thus instantly establishing the unusual fairness of Lt. Williams the prison guard and the good-heartedness of Jimmy the man. This is further accentuated throughout the movie by Williams’ treatment of Carter; and culminates in a dedicated shot of him at the back of the courtroom, visibly happy for Carter at the announcement of his acquittal.

*To be clear, Brown’s performance in this inverted role is not in question, for he plays it well (which I find to generally be the case, i.e. that actors perform their inverted roles as believably as they do their more usual character type). Rather, the ridiculousness is to have cast Brown of all people in this role, for the (obvious) reasons discusses above.

*Williams, of course, cannot know that Carter is innocent; and, with evident honesty, says as much when Carter asks him if he thinks he’s guilty. Note that in The Shawshank Redemption, in which Brown plays the horrendous prison guard, the imprisoned protagonist (Andy) has also been wrongly convicted of murder.

Thus, to clarify, Clancy Brown went from the uber-bastard prison guard Byron Hadley, a character who – from his very introduction – made the viewer dread the thought of ever being imprisoned; to an implausibly kind prison guard whom anyone would dearly wish for were they imprisoned. The fact that The Shawshank Redemption is a highly popular film, and that Brown’s face must be inextricably associated with his bastardly role in it, makes this role-inversion one of the most absurd—a practical announcement of the actor’s role-inversion.